Written by Lillian Stockford

The taking away of one’s privacy is in many ways dehumanizing. It removes a person’s freedom and creates an environment where it is a struggle to truly be an individual.

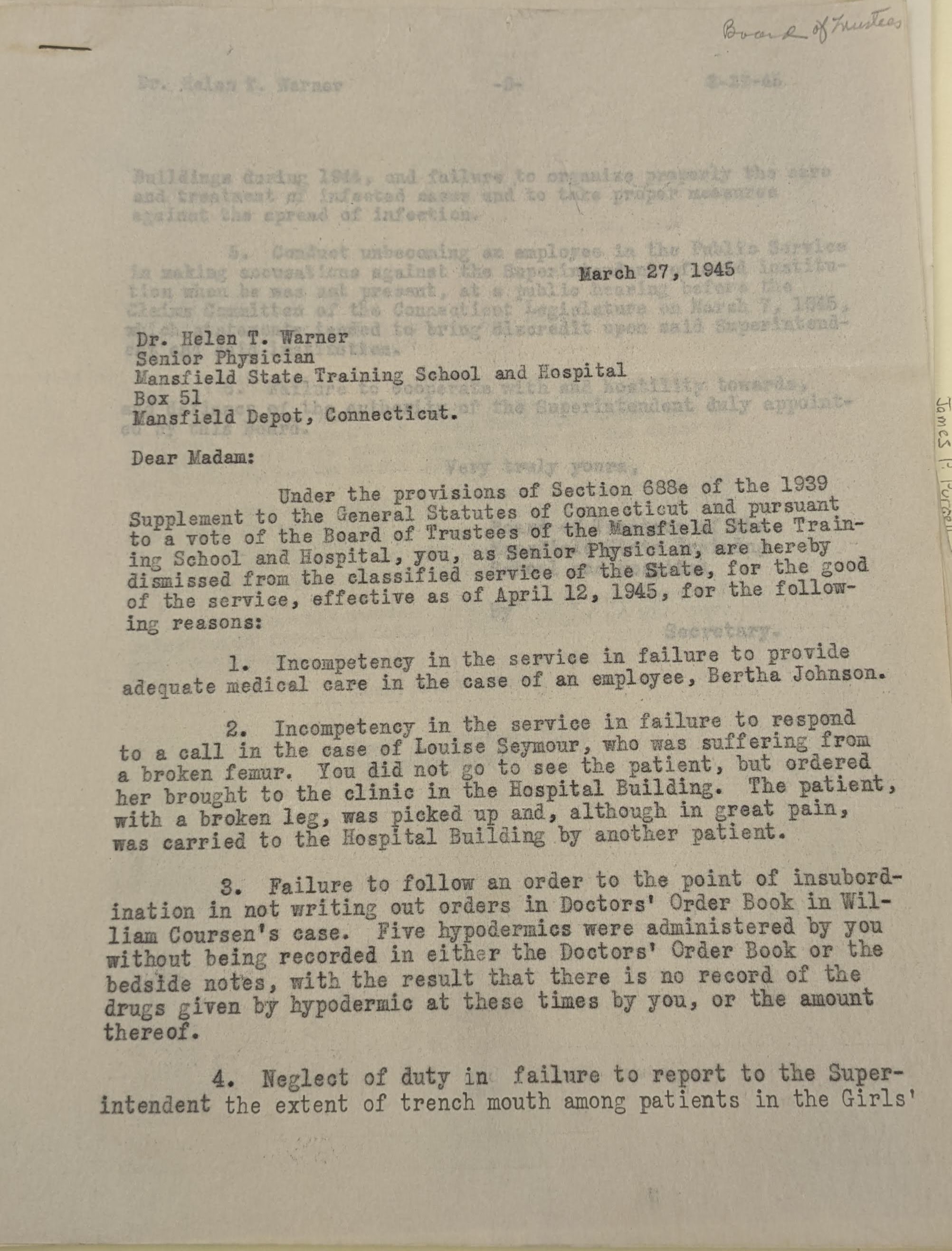

Looking at the Mansfield Training School dorms, a few descriptors come to mind. A minimum security prison. A place stripped bare of personalization. Sterile and unwelcoming.

The image of the children’s dorms is especially damning. The beds are so close together that they almost form one continuous bunk. The lack of privacy and personal effects. One may argue that it was for resident safety. However safety does not have to mean inhumane. Not giving residents any space to have as their own does not make them safer, it simply takes away a basic human need. It exposes the insidious belief that people with disabilities do not need or deserve privacy. And this belief further leads to a lack of respect and understanding.

Even in spaces meant to be “homey” there is a cold feeling. The decals of cartoon animals on the walls of the children’s dorm do not do much to brighten the space. If anything they make the space feel more empty as they make the deficits of the room more obvious. There was a “day room” to function as a lounge space for residents but it was also depressingly bare: empty tile floors, minimal furniture, and naked walls come together to make a less-than-comforting environment. It feels almost clinical, like a doctor’s office waiting room. The “day room,” much like the dorm room, lacks warmth and a feeling that this is a home. The institution may have handled medical matters but it also was a place of living for over a thousand people at its peak and it is clear that making the institution a comfortable home was not valued by the administration.

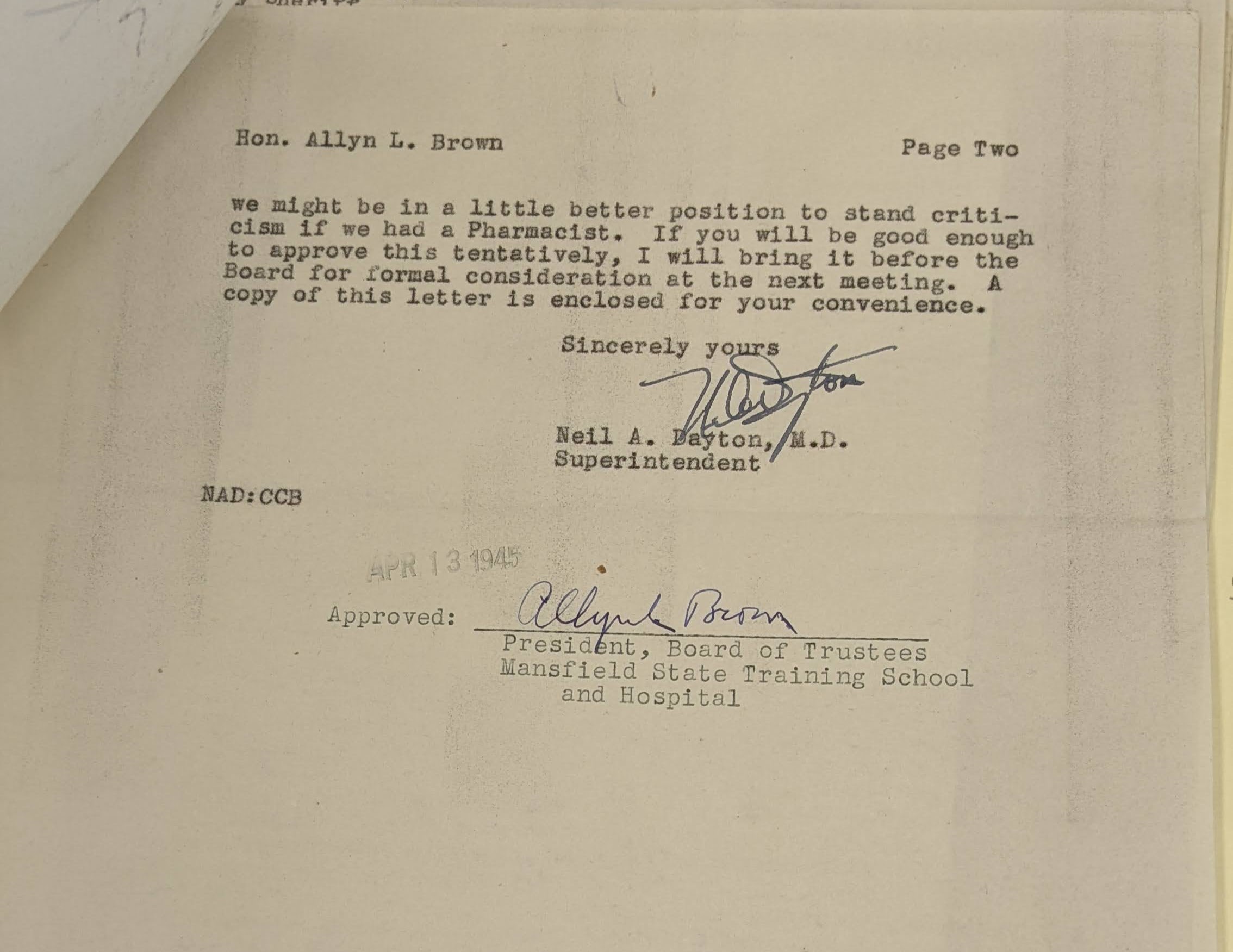

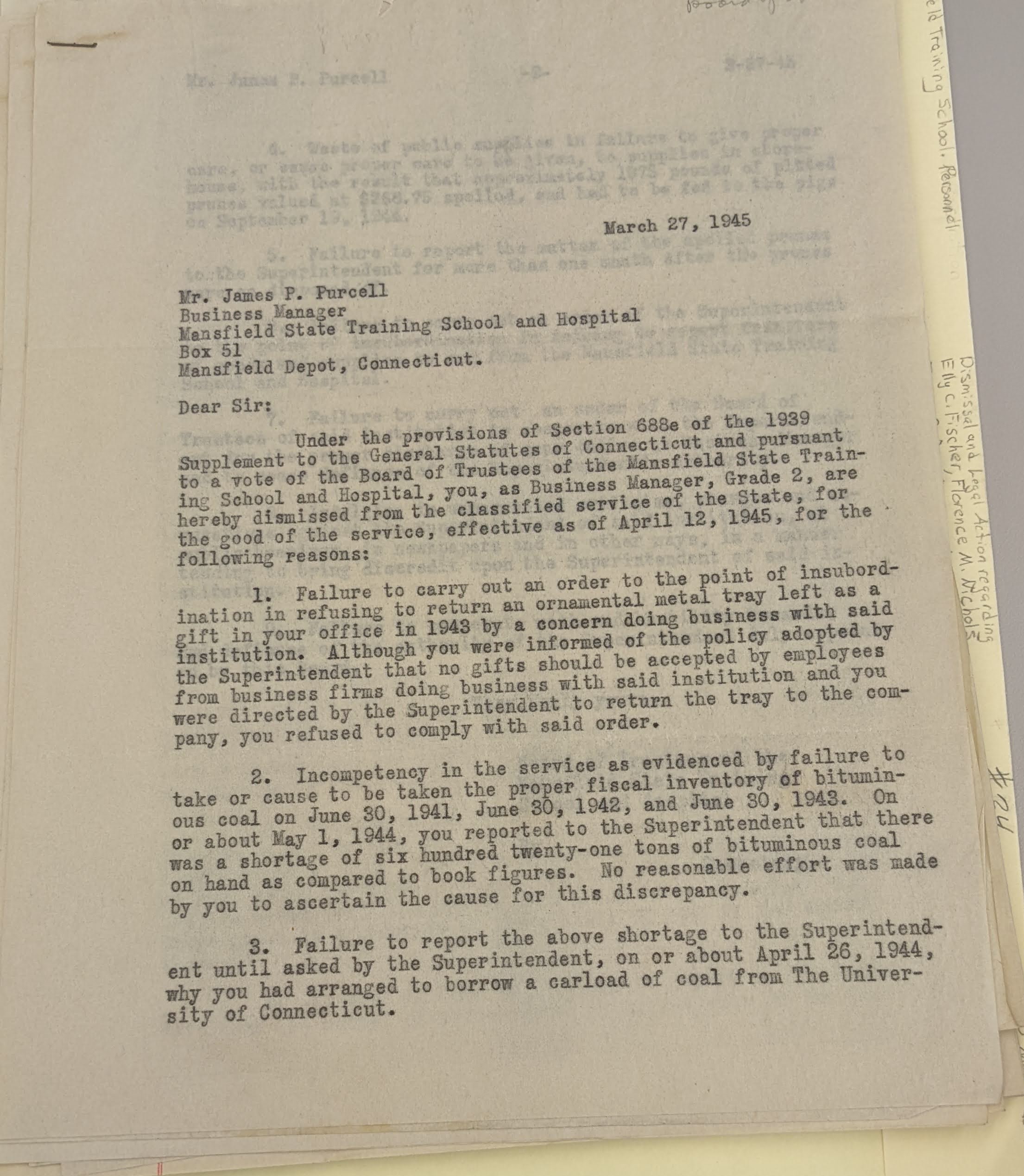

It is also interesting considering the largeness of the superintendent’s home. It has pillars, a feature that tends to be associated with power and wealth, but the residents can’t have two feet of space between the beds? Can’t have stall doors in the bathroom? When placed side by side it is disturbing to see the differences. MTS was a home for its residents. Many didn’t have the option to go anywhere else if they found their lodgings less than satisfactory. For those who had entered the institution as young children or toddlers, MTS was the only home they had ever really known. For those unequipped by the system with the tools to leave, there were not many options available. For children, even less so, as some were wards of the state and given no choice concerning where they lived. Some residents had medical needs that stopped them from leaving, as the resources were not available outside the institution. They were living in a system that pushed them towards institutionalization and then failed to support them once they were admitted. A system that did not value choice and freedom.

It speaks to a larger trend of not viewing residents as people with feelings and preferences.

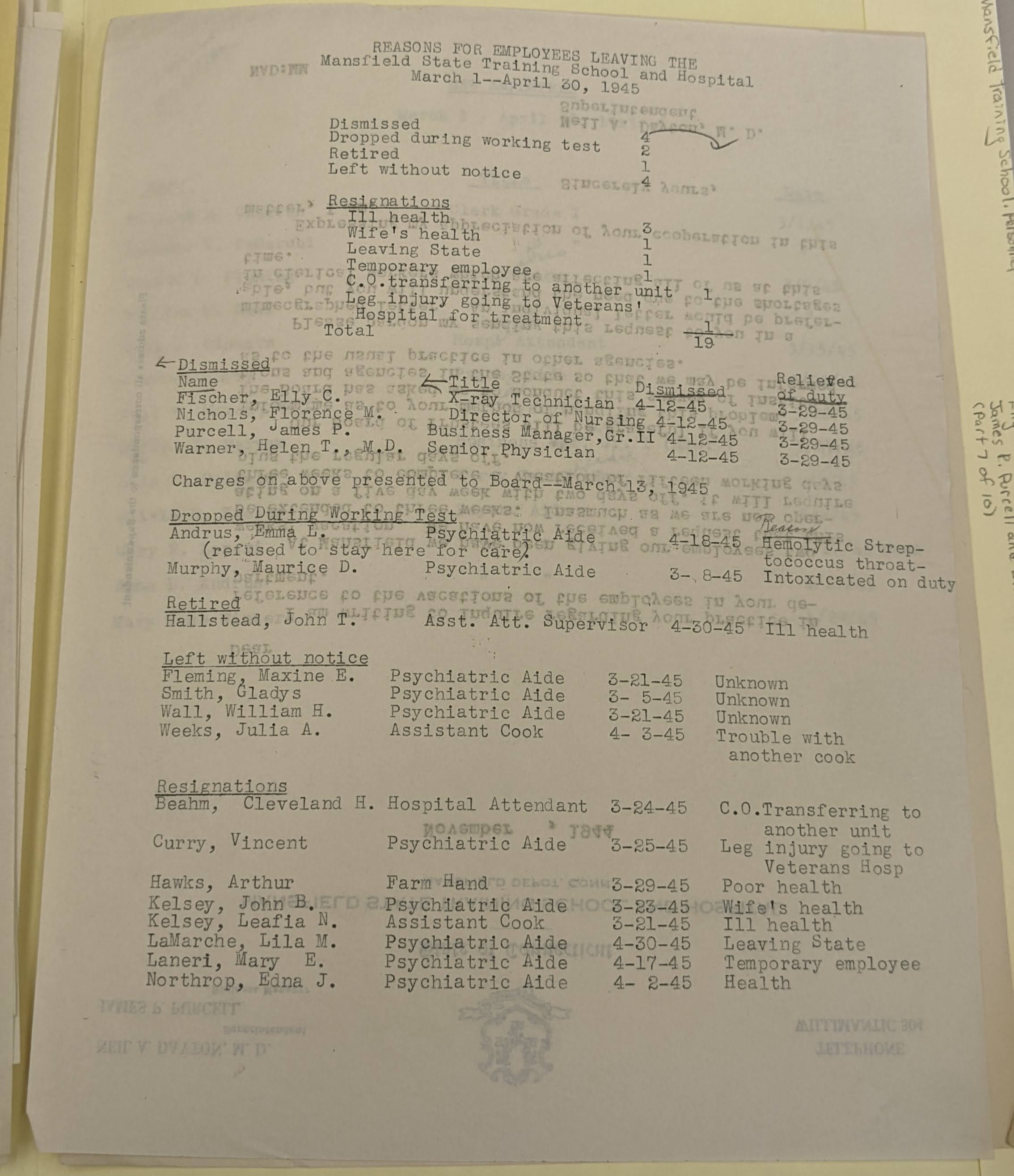

It also makes one wonder why it was necessary to have the beds so close together. Was it simply a lack of care? Or does it allude to a larger systemic issue of overcrowding? Not all of the dorms had this sort of layout, though the others were not objectively good, which I will come back to later. If a facility has to have this sort of layout in order to fit the number of people they need to then there is inherently a structural issue. This sort of design should not have been considered a norm but rather a failure.

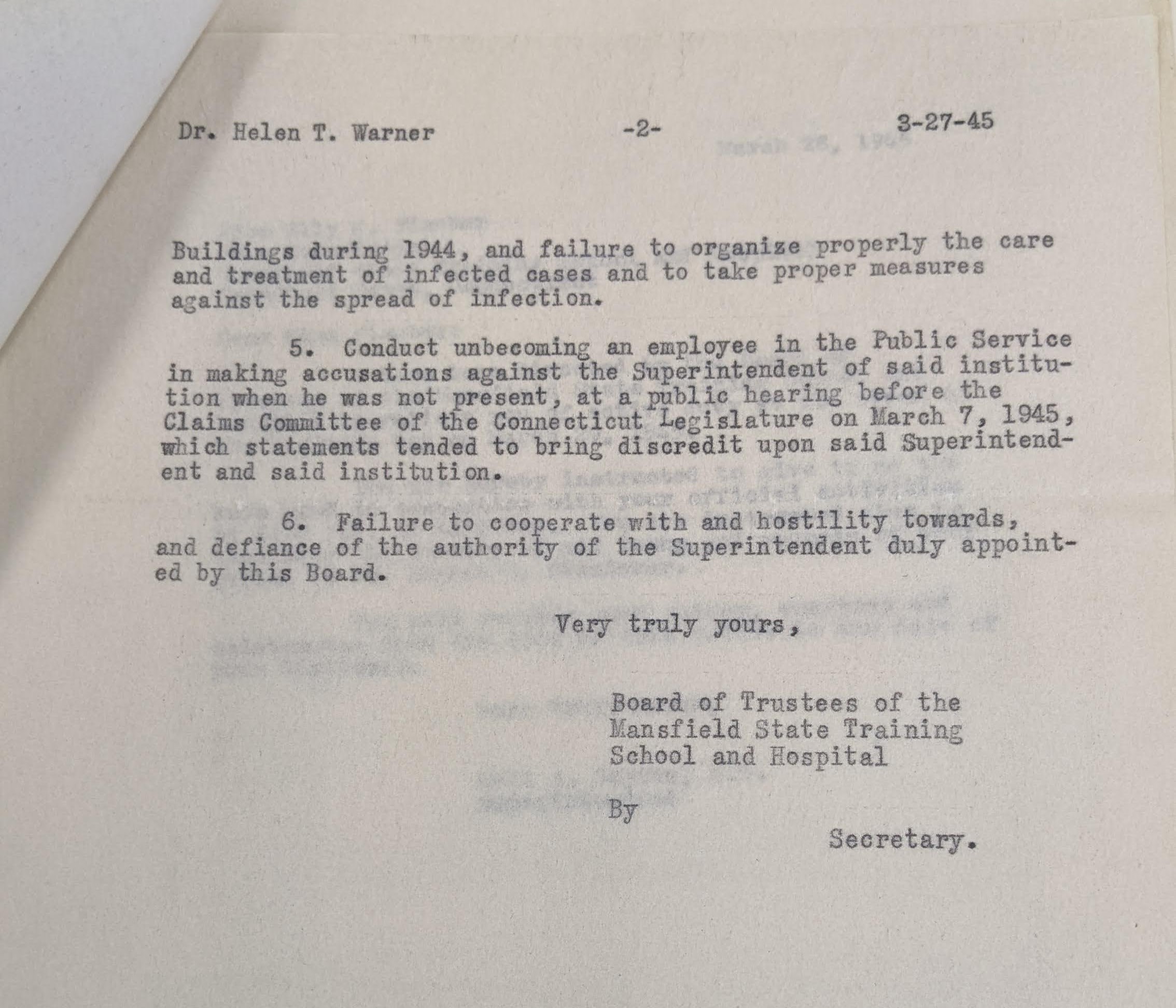

This is a picture of a dorm called the Merritt Dorm, from 1956 which is better than the children’s dorm, with at least wall structures present, but it is still not adequate. Better than nothing is still not good. There is still a complete lack of privacy, just assuaged a bit by the cubicle-style walls. It still does not look like a home or even a dorm—still no privacy, a feeling of overcrowdedness, and blank walls.

Even with improvements, the systemic issues within institutions still leak in. Even the newer, better option does not fix the issue, merely putting a bandaid on it. There is a lack of respect for residents, for their needs, for their wants, and for their space. Especially if you consider the length of time that people were living in the institution. It was generally not as short as a hospital stay. People were entering the institution as young children and then not leaving, living in these dorms for decades upon decades. It is also important to consider the accessibility of these dorm setups. The tight spaces would not have worked well for residents who use wheelchairs or other mobility devices. The dorms allude to a larger trend with the institution of not considering the comfort of residents. Of not giving them the freedoms they would otherwise have been afforded. They demonstrate the systemic failures of the institution and a lack of respect for the people who lived there.