Written by: Gabby Disalvo

Gratitude is a powerful feeling. It can be based on how you are treated, how you perceive the world, and how you see yourself. Gratitude can come from a present time, past event, and “anticipatory gratitude” of the future. While visiting the Willowbrook Archives, I experienced all three tenses in just 48 hours. On June 17th, Professor Brueggemann and I visited the College of Staten Island. I was amazed that a place which felt so familiar, could also feel foreign at the same time.

I was born and raised in Staten Island. I have attended numerous events at CSI and have often heard about the offerings and deep history that the school holds. I have also heard many (vague) stories about the Willowbrook institution. I knew it existed, was a bad thing, and was shut down when the “badness” was revealed. I describe my knowledge this way because I now know how bare minimum my understanding was.

Professor Brueggemann and I had the opportunity to get a “walkthrough” of part of the Willowbrook Mile from historians, Dr. Catherine Lavender and Dr. Nora Santiago, the Willowbrook Legacy Project co-directors. They walked (and rolled) us to some of the markers on the trail and shared their experiences of creating the WM and any history that they felt was notable to share. They told of the horror stories they have heard, especially from a staff member from Willowbrook. They described the documents they’ve read, images they’ve seen, and the hidden details that Staten Island’s “rich” history has buried deep in the archives.

While passing a main area on CSI’s campus, I was quickly brought back to a memory of the theatre center where I used to have recitals for my dancing school as a child. This building now had a WM marker in front of it. I was struck with such surprise that I had been surrounded by this history then, but I had no idea. Making this connection was my first major moment of past gratitude during our visit.

The following day Professor B and I attended a rally to advocate for the government to keep their “hands off Medicaid”. We gathered in front of a building which stores the Willowbrook Archives. This is also the location of the first WM marker, which is angled to face the area of the building where these archives are. I was surrounded by 200+ people, all with varying connections to disability. For example, some were individuals with intellectual disabilities that came with friends and family, some were members of group homes, some were family members of residents of Willowbrook, some were Medicaid users (like me), and some were advocates because of their professions related to disability (also like myself). Although we were attending the rally for different reasons, we were all there to fight for our lifelines, our Medicaid benefits. Being surrounded by this passionate energy initiated my present gratitude for the strength of this community during this trying time.

Gabby at a rally, advocating to protect Medicaid.

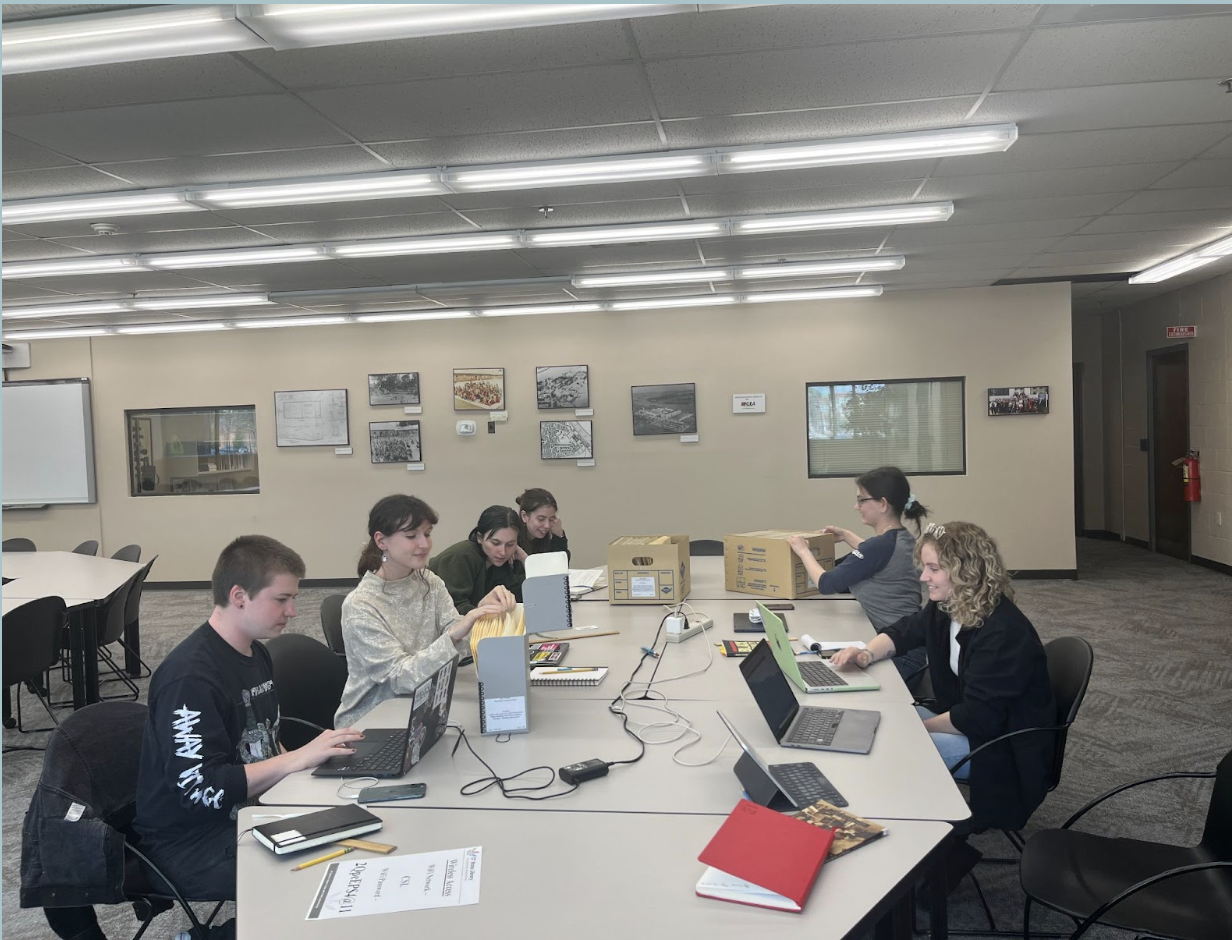

After the rally, Professor B and I (and my mom) went into the library and up to the second floor to the Archives and Special Collections area. Initially, I thought the experience would be like visiting the CSL Archives. The air was chilly and felt aged, like a childhood bedroom that has been untouched for many years. I had a lot of built-up tension from the anticipation of sifting through this new material, the awkwardness of having my mom join us on this visit, and the struggle of trying to separate my mind from the concluding rally just outside. As we settled down at the table and opened the first set of documents, I felt my mind dive headfirst into the material. I began painting a story in my mind of what Willowbrook was like.

Me trying to immerse myself in the reading and imagine life at Willowbrook.

As a disabled individual, I have had to learn to advocate for my abilities, my rights, and my independence. However, despite the progress in our world, there are many instances where the systems in place or people of power assume that I am not capable of this on my own. Although my experiences are not nearly as extreme as how individuals were treated at Willowbrook for far too long disabled people have been excluded from discussions and decisions about their lives. Reading the ways that the residents were described and seeing the compilations of files highlighted the accessibility that we have today.

The more I read, the more I was reminded of the immense gratitude I have for my lifestyle. For instance, after our visit with the Willowbrook Archives, I took an accessible Uber to lunch at an accessible restaurant, then used the accessible bathroom there, and finally, took an accessible city bus home. I am endlessly grateful for the level of accessibility in our modern world. I do not mean access in just the “structural” sense, but also in the way that society treats disabled people, especially the United States. Although disabled people still lack many equal rights, the world has gradually become more inclusive and sees that we (disabled people) are to be treated with the same value, dignity, and respect as any other person.

![[Visual Description: A collage composed of both digital and physical materials. In the center of the collage is the blueprint for the basement of Knight Hospital, with a red “You Are Here” pin placed in the hallway between the waiting room and the mortuary. Surrounding this map are ink drawings that I doodled in my notebook while reflecting on the archives, crumpled pieces of paper, and photographs taken of the inside of the Longley School, and Superintendent’s House on site at Mansfield Training School. The oppressive mint green of the walls frames the collage, alongside images of manila folders, wooden rulers, metal paper clips, clocks, and climbing ivy. In the top left corner there is a photograph of the restraint logs found at the state archives. In the bottom right corner, there is a Massachusetts ruling about the treatment of those who die in institutions. The background of the collage is a textured mess of brick and paint and scribbles alongside redacted documentation.]](https://mansfieldtrainingschool.research.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3976/2023/08/screen-shot-2023-08-31-at-9.54.44-pm.png)

![A photo of the blueprint of the basement of Knight Hospital. The paper is textured and off white, and the floor plan is outlined in purple-ish blue ink.]](https://mansfieldtrainingschool.research.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3976/2023/08/screen-shot-2023-08-31-at-9.57.29-pm.png)