Written By Ashten Carter

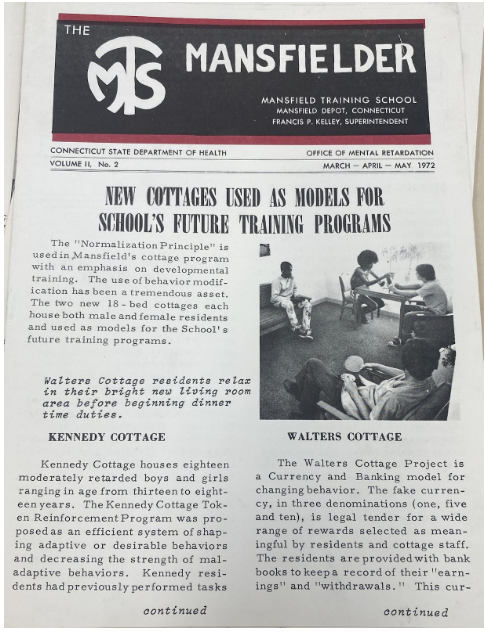

When I first found out about Mansfield Training School, I felt a calling. Frustratingly, there was not much information I was able to gather on the facility’s history. When I googled Mansfield Training School, the historical information was overshadowed by results containing phrases like “Insane Asylum,” “Most Terrifying Abandoned Psychiatric Hospital,” “Scariest Place in Mansfield,” and “Paranormal.” Perhaps the one word I saw the most was the word “haunted.” Google assumed I wanted a ghost story, and hawked the now defunct institution as one of “The 8 Most Haunted Places in Connecticut,” or claiming it to be a “Haunted Asylum from Hell.”

I felt as though I was coming up empty, except for the bitterness I felt crawling up my throat. I did not want to be sold a sensational story. It felt exploitative and disingenuous. The institution only closed 30 years ago but it was starting to seem that the humanity of the site had crumbled away, or peeled off with the paint. More accurately, Mansfield Training School’s clinical environment was further sterilized by the act of forgetting. It was easier for the public to grapple with the ruins of the “Depot Campus” if they could call it haunted. Most people did not want a glaring reminder of what happened there. Maybe they wanted to rationalize away the hurt. When this reconciliation could not be done, maybe they turned to forgetting. Perhaps it was a community’s wounded attempt at understanding a site of harm.

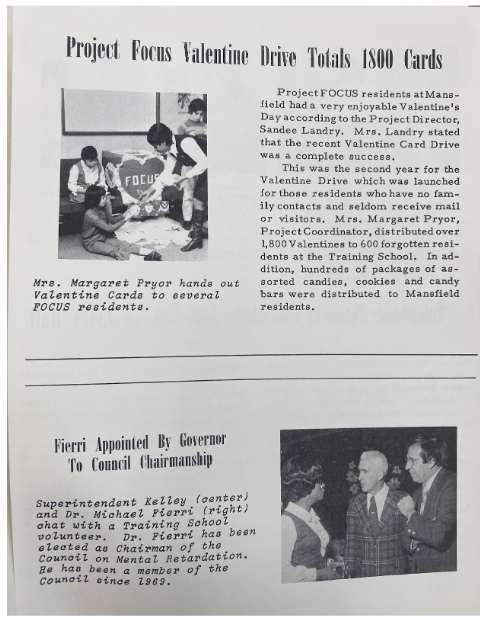

Macabre fascination was not what drew me to the project. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I wanted to learn the history and see the buildings, to know the residents and the administration. I was searching for kinship with people I would likely never meet. That’s what led me to the archives. When Jess and Brenda gave a presentation on research they had done on Mansfield Training School, I was overcome with curiosity. I had the opportunity to ask questions and realized I had more questions than I could have imagined. I wanted to absorb everything that I could. So when the chance came to visit the Connecticut State Library, I was…. excited? Is excited the right word? Does it matter if it is fear or excitement if they both ache the same way in your chest?

Brenda and Lily were kind enough to give me rides to and from the archives. Our commutes to Hartford were usually filled with apprehension and caffeine. The rides back were consumed with exhausted reflection. Under the guidance of the archivists, we were able to get glimpses of MTS. Pouring over the documents and photographs in the archives was an experience unlike any other. We found a need to comb through everything we could get our hands on, and piece together snippets of narrative where we could. There was a hunger, a desire to take in as much as we could during the limited time we had to spend, even when the material was difficult to read. It was as if we held our breath for the chance at accessing information that may let us better understand the weight of the information. And once we were finally able to exhale, we did so over snacks and conversation. We shared thoughts, questions, jokes, chocolate bars, and stories. The archives were intimidating, but the research team was always sweet and supportive of one another. Even though our team was only able to meet in person a handful of times during the summer, it was unforgettable to share that time and space. I was seeking kinship between the lines of documentation and pressed between manila folders. I found it in fruit snacks, pet photos, doodles, and carpools.

Still, there was the matter of access. Mansfield Training School was so close to where we live and work. Its history impacts many features of the local area today, and yet we had almost no access to information as members of the public. Frankly, we may not have been able to determine where to look without the resources and connections provided by the university. If not for the opportunity to take in the archives, we would only know Mansfield Training School through the videos uploaded to youtube by self-proclaimed urban explorers and paranormal enthusiasts.

That is why experiencing the archives was so captivating and so vital to the mission of our project. We maintained the goal of creating access to the information. In all its mess, with all its nuance and complexity. No sensational “ghost stories” or “haunted tales” to explain what we can’t understand. We would not assist in the collective forgetting of Mansfield Training School, just as many other community members who remain impacted by what happened there. We found many versions of Mansfield Training School and its key figures throughout the 133-year reign. It doesn’t take courage to call a place haunted or create an attraction out of a site of great pain. The truly brave feat is in digging deeper, asking “why?” and grappling with what you may find.