The following is a slide show presentation of a live reading of Superintendent MacNamara’s 1994 article on the closing of Mansfield Training School. To interact with this piece, please click the embedded link below, select the audio button in the upper left-hand corner to begin the audio, and click through the piece to see the text from the readers.

Archives

Places of Waiting

Written By Ashten Carter

![[Visual Description: A collage composed of both digital and physical materials. In the center of the collage is the blueprint for the basement of Knight Hospital, with a red “You Are Here” pin placed in the hallway between the waiting room and the mortuary. Surrounding this map are ink drawings that I doodled in my notebook while reflecting on the archives, crumpled pieces of paper, and photographs taken of the inside of the Longley School, and Superintendent’s House on site at Mansfield Training School. The oppressive mint green of the walls frames the collage, alongside images of manila folders, wooden rulers, metal paper clips, clocks, and climbing ivy. In the top left corner there is a photograph of the restraint logs found at the state archives. In the bottom right corner, there is a Massachusetts ruling about the treatment of those who die in institutions. The background of the collage is a textured mess of brick and paint and scribbles alongside redacted documentation.]](https://mansfieldtrainingschool.research.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3976/2023/08/screen-shot-2023-08-31-at-9.54.44-pm.png)

The floorplan was not the most remarkable thing that I saw in the archives. At first glance, there was nothing extraordinary about the basement of Knight Hospital. This was not like the documents that puzzled me, the images that startled me, and the narratives that captivated me. Yet, this blueprint was the piece that stuck with me. I suppose that is because there was no room (literal or figurative) for interpretation. It was a floor plan. There was supposedly no reading between the lines. There was no speculating about who created it, or how they must have felt, or why. It was objective, unlike so many of the documents we had spent the summer combing through. There was the boiler room, the clinics, the bathrooms, the storage room, the lab, the corridors, wheelchair ramps, the stairways, the garbage shed all neatly outlined and labeled. Precise down to the measurements.

And then there was the waiting room right next to the mortuary.

Holding that paper in my hand is not a feeling that I’ll soon forget. It was as though time stood still for a moment. And in a way it had. I was imagining being in a place of “waiting.” A place where time stood still.

How would it have felt to be sitting in those chairs?

What did it feel like coming into the hospital from the dorms?

Would they tell you why you were there?

How would it feel to leave the clinic, knowing no one ever returned from the door just down the hall?

How many friends had they lost while interned by the state?

What were their names?

Where are they buried?

Institutionalization reminds me of that waiting room. Institutions have historically been a place to hide away society’s “undesirables.” To the general public, there’s an “out of sight, out of mind” approach to those who are institutionalized. It’s why we find these facilities in such remote areas. It makes it easier to forget about the people that were already forgotten. However, for those who live in institutions, there is no putting it out of your mind.

Mansfield Training School was an influential institution, a contributor to the local economy, and “the only option” for many Disabled people and their families. It was also a warehousing operation; it was a “place of waiting.” It, like other institutions of its kind, was where you went to die.

Just as much as I wondered what it would be like to sit in that waiting room while the facility was in operation, I couldn’t help but wonder what it would be like now.

What color is the peeling paint?

What would it be like to see the records of former residents strewn across the floor?

30 years after the closure of Mansfield Training School, Knight Hospital stands overgrown and decaying. The records stored in that same basement have been deemed ‘irretrievable.’ While institutionalized, the residents’ stories were kept hidden from the outside world. Even now that the institution has closed, their stories remain untold.

Waiting is the very nature of being institutionalized. We wait for funding for community-based options. We wait to hear from family, if we have any. We wait for the next meal or the next way to pass the time. Sometimes, time passes us.

Many residents spent decades of their lives at Mansfield Training School, an institution that claimed to specialize in caring for those with disabilities. In actuality, institutions like MTS specialized in waiting.

Did the residents of MTS know the waiting room is for the clinic?

Did they fear that it just as easily may have been for the morgue?

![A photo of the blueprint of the basement of Knight Hospital. The paper is textured and off white, and the floor plan is outlined in purple-ish blue ink.]](https://mansfieldtrainingschool.research.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/3976/2023/08/screen-shot-2023-08-31-at-9.57.29-pm.png)

In the Archives…

Written By Dr. Brenda Brueggemann

I’m not a very patient person and my attention span has some challenges since I’m always thinking of (way too many) projects and ideas at any one moment. And so: I’m not a Good Person in the Archives.

I knew that already about myself. I had tried it before with numerous (significant and scintillating but still abandoned) Deaf studies/history projects in the past. Sure, I’m trained with a PhD in the philosophy, theory, and practice of the ancient art of Rhetoric, So, in essence, I had all the “basic skills” to do this kind of work. On paper.

But my imagination has always wanted to overtake the archives, to fuss with the fact-finding, and to dog the detailed and deliberate march through The Records in pursuit of Historical Truths. I would always get impatient and distracted, my storytelling self taking over the driver’s seat down the archives highway, eating up the rest of the bag of chips.

Being in and “doing” the MTS archival work was hard on me then, needless to say.

I was cold in there – all the time. Both physically and probably also a little spiritually. The air conditioning was overwhelming in the summer and then dead-air damp chill saturated the space in the winter. The closed-in feeling was quite claustrophobic. The Connecticut State Library (CSL) archivists were watching us all the time –and that surveillance rubbed on my edges. My mind wandered, a lot. I couldn’t stop thinking about: the chocolate peanut butter granola protein bar I’d left in my backpack at the locker outside the archives; or the abandoned deli in the corner of our window view at the Connecticut State Library Archives warehouse location in near-downtown Hartford, CT. (possibilities of a good grilled cheese sandwich haunted me at every visit); or the red comb someone had left in the bathroom there (that had now been there for over a year of our visits); or the Colt Gun Factory exhibit on the CSL Archives meeting room wall; or the rickety-rickety old school rolling-fenced gate that chugged its way back, so very slowly, to let us into the dilapidated and patchy asphalt “parking lot” at the archives; or the parents and kids at the school right next to the archives building who convened for pickup in mid-afternoon (and wouldn’t then allow us exit from the archives at that time). I was distracted.

But then again, I wasn’t. I was also finely focused, riveted, operating on High Purpose.

I reveled in (and largely remembered) the remarkable details of almost every team conversation we had within the CSL Archives. I came to know everyone’s favorite snack options. The community we created in the archives –doing this work, together, and troubled, and important, and a little terrified – these are the things I most take away from (and with) it.

Why I’m Here -Brenda

I’m here, on and in this project, because I simply couldn’t not be. I didn’t choose the project (like many of the fabulous undergraduate research team members did) – it chose me.

I had done some other community-related disability advocacy and activism work in Ohio (while on the faculty at Ohio State University for 21 years) and in Kentucky (while also on the faculty at the University of Louisville for 3 years). But those were more containable projects with goals and known limits and ends. (See: Voices Together: The Art as Memory Project)

The MTS Memorial and Museum @ UConn Project is far bigger and more unknown than any of those previous projects I’ve encountered and engaged in. The MTS Project is a case of “research” finding me – rather than me setting out on a predetermined research path. It’s something like “research at first sight” (akin to “love at first sight”) where I was utterly swept off my feet and then the project just overtook me.

And yes, that’s a little complicated and icky too. Love and research can be like that.

I wasn’t expecting to take on such a large-scale, deep, wide, troubling, meaningful project at this stage in my fairly long academic career. I was thinking more about coasting into a couple of grand finale style essays and invited cameos for my last years as an academic – with 25 years now in the field of Disability Studies. But then: Jess and I literally fell into this project with a half-hour independent study conversation in my office late in September 2021. The world kind of flipped over on that day for me.

I am a disability studies scholar – and a disabled person – for my lifelong academic career. I am of the “first generation” of such folx in higher education. The MTS project brings together the best of the skills and things I’ve worked on, worked towards, advocated for, and taught about in my 30-year faculty career:

- carrying out advocacy that is based on community;

- engaging disability rights activism that blends study with struggle, education with the public;

- re-telling and excavating buried disability history/ies;

- combining archival research with narrative techniques and analysis;

- working closely with student researchers and writers to learn, create, grow through the material together

I’m home. I’m here.

My Time at the Archives

Written By Ally LeMaster

When I think back to the archives, I think about the hazy lighting.

How the documents were lit up by sterile fixtures. The whole building seemed muted, except for the latex-free, oversized green gloves.

After hours of pouring over archives, my hands felt like a layer of the past rubbed off on my fingers— that somehow the particles in the air at Mansfield Training School carried from all these years to end up in the present.

I remember the smell of the old transfer paper and wondered if that’s the scent that perforated MTS too.

Mildew and must.

I wanted to know who touched the papers before me and what their hands did before and after. Were their hands healing?

Did they cause harm?

Or were their hands simply bystanders to horrors that went on there?

I remember trying to stop myself from asking questions that could never be answered. Just to stick to words written on the paper in front of me.

But there were still questions on top of questions.

I remember combing through every single document because I was scared to miss the important detail. Like if I read every single word, I could actually make sense of what happened. But I couldn’t find those words because sometimes actions won’t always have meaning behind them.

I would always catch myself looking up at the face of the archivists. How they talked firmly about the present, but the research team was sunken deep in the past.

Mostly, I think back to the relief and worry that went through me when it was time to leave.

In the archives, you absorb almost a decade’s worth of information in a day and have to go back home to a false sense of normalcy. I remember how my days in the archives stuck to me like the embrace of a shrunken sweater.

I’d pull up to my house exhausted.

My dad would ask me how my day at the archives went.

Every detail of every document swarmed my head, from the restraint logs to employee guidebooks. The sad, the grim, and the troublesome stories told in the archives were always at the tip of tongue.

But I knew I had to pull away from the question. I didn’t want the information to haunt him like it did me.

“My day at the archives was good, Dad.”

And I’d go to my room as if nothing ever happened.

Taking in the Archives…

Written By Ashten Carter

When I first found out about Mansfield Training School, I felt a calling. Frustratingly, there was not much information I was able to gather on the facility’s history. When I googled Mansfield Training School, the historical information was overshadowed by results containing phrases like “Insane Asylum,” “Most Terrifying Abandoned Psychiatric Hospital,” “Scariest Place in Mansfield,” and “Paranormal.” Perhaps the one word I saw the most was the word “haunted.” Google assumed I wanted a ghost story, and hawked the now defunct institution as one of “The 8 Most Haunted Places in Connecticut,” or claiming it to be a “Haunted Asylum from Hell.”

I felt as though I was coming up empty, except for the bitterness I felt crawling up my throat. I did not want to be sold a sensational story. It felt exploitative and disingenuous. The institution only closed 30 years ago but it was starting to seem that the humanity of the site had crumbled away, or peeled off with the paint. More accurately, Mansfield Training School’s clinical environment was further sterilized by the act of forgetting. It was easier for the public to grapple with the ruins of the “Depot Campus” if they could call it haunted. Most people did not want a glaring reminder of what happened there. Maybe they wanted to rationalize away the hurt. When this reconciliation could not be done, maybe they turned to forgetting. Perhaps it was a community’s wounded attempt at understanding a site of harm.

Macabre fascination was not what drew me to the project. In fact, it was quite the opposite. I wanted to learn the history and see the buildings, to know the residents and the administration. I was searching for kinship with people I would likely never meet. That’s what led me to the archives. When Jess and Brenda gave a presentation on research they had done on Mansfield Training School, I was overcome with curiosity. I had the opportunity to ask questions and realized I had more questions than I could have imagined. I wanted to absorb everything that I could. So when the chance came to visit the Connecticut State Library, I was…. excited? Is excited the right word? Does it matter if it is fear or excitement if they both ache the same way in your chest?

Brenda and Lily were kind enough to give me rides to and from the archives. Our commutes to Hartford were usually filled with apprehension and caffeine. The rides back were consumed with exhausted reflection. Under the guidance of the archivists, we were able to get glimpses of MTS. Pouring over the documents and photographs in the archives was an experience unlike any other. We found a need to comb through everything we could get our hands on, and piece together snippets of narrative where we could. There was a hunger, a desire to take in as much as we could during the limited time we had to spend, even when the material was difficult to read. It was as if we held our breath for the chance at accessing information that may let us better understand the weight of the information. And once we were finally able to exhale, we did so over snacks and conversation. We shared thoughts, questions, jokes, chocolate bars, and stories. The archives were intimidating, but the research team was always sweet and supportive of one another. Even though our team was only able to meet in person a handful of times during the summer, it was unforgettable to share that time and space. I was seeking kinship between the lines of documentation and pressed between manila folders. I found it in fruit snacks, pet photos, doodles, and carpools.

Still, there was the matter of access. Mansfield Training School was so close to where we live and work. Its history impacts many features of the local area today, and yet we had almost no access to information as members of the public. Frankly, we may not have been able to determine where to look without the resources and connections provided by the university. If not for the opportunity to take in the archives, we would only know Mansfield Training School through the videos uploaded to youtube by self-proclaimed urban explorers and paranormal enthusiasts.

That is why experiencing the archives was so captivating and so vital to the mission of our project. We maintained the goal of creating access to the information. In all its mess, with all its nuance and complexity. No sensational “ghost stories” or “haunted tales” to explain what we can’t understand. We would not assist in the collective forgetting of Mansfield Training School, just as many other community members who remain impacted by what happened there. We found many versions of Mansfield Training School and its key figures throughout the 133-year reign. It doesn’t take courage to call a place haunted or create an attraction out of a site of great pain. The truly brave feat is in digging deeper, asking “why?” and grappling with what you may find.

The Paper Trail of Charitable Giving: Implications of Donation, Benevolence, and Gratitude in the Institutional Setting

Written by Madison Bigelow

By the time I arrived at the Connecticut State Archives warehouse for the first time to begin my work on the MTS Memorial Project, I had already formed a number of expectations as to what I might see kept in those boxes (which included, but were not limited to: government proceedings regarding the institution’s closure in 1993, lots of grainy, black and white photos, and tons of carework guidelines for the facility’s employees). What I didn’t expect, though, was to be handed a box filled with several hundred donation receipts that were maintained throughout the 60s.

In reality, these receipts took the form of letters. In each document, the letter addressed the donor, thanked them for their contribution(s) to Mansfield, explicitly made note of each item and its quantity that was received, and assured the donor that their gifts will be greatly appreciated by the ‘boys and girls’ of MTS.

The last paragraph, which appears in some iteration across every receipt we found in the archives, states: “We certainly do appreciate such a large and useful donation as our boys and girls can always use good clothing. It is nice to know that our children here at Mansfield are remembered and we take this opportunity to thank you on their behalf.”

These thank you letters offer an interesting window into the life of an MTS resident during the 60s at first glance. However, the more receipts I uncovered, the more questions arose. For instance, I am still attempting to understand why we – historians, archivists, scholars – have these documents. Why were these letters kept by the MTS administration in such detail? And only for these years? Why do these letters seem to only have been written in a very small time frame? And what does this mean for the legacy of MTS? For institutional legacies at large?

Perhaps the archivists that went on-site at Mansfield to collect these ‘lost’ documents in ~2010 were only able to salvage a portion of the donation receipts that were produced by the MTS administration. We do know for certain that there are still many artifacts left on the floors of the Mansfield campus buildings deemed forever ‘irretrievable’ as per the state of Connecticut. Considering that the archived letters we do have access to, though, were all written within the same X YEAR span with no temporal outliers, it feels safe to assume that this clerical venture was only a short blip in MTS’ much longer history.

Despite this being such a small blip in MTS’s greater legacy, the insights that these documents offer are potentially quite valuable to understanding institutional functionality in the 20th century.

As Paul K. Longmore writes in Telethons: Spectacle, Disability, and the Business of Charity, “in order for givers to have regular occasions on which to ritually reassure themselves of their moral health and social validity, it was necessary to perpetuate the social and moral invalidation of people with disabilities” (83). I do not seek to diminish the kindness of the said ‘givers’ in question, nor the assumed benefits that residents of MTS reaped as a result of these donations, but I rather aim to question: why do these records exist to such minute specificity? One possible answer to this question is promoted by Longmore’s observations about the American Telethon; the paper trail of charitable donation aims to continually affirm differences that exist between members of an institution and its counterparts on the outside. In other words, letters built a paper bridge that connected the interior world of MTS and the town of Mansfield on its periphery.

By this logic, these “thank you” notes are a physical receipt of performed benevolence. Since residents were regarded as incapable, incompetent, immoral, or otherwise just underserved by their institution, giving becomes an act of distance. The donation of used goods creates space between residents and community members and subsequently justified social, economic, and spatial power dynamics that further insulate training schools, writ large, from the greater towns they are a part of.

Thus, understood in Mansfield’s context, Longmore’s argument that “perennial [objectification] of charity in order to reassure putatively normal Americans of their own individual moral health, [and] of the continued vibrancy of the American moral community” rings true (83). This distance validates feelings of moral superiority and indicates that, as a part of this performance of benevolence, such tight recordkeeping was encouraged by Mansfield’s administration, if only for a small window of time.

In addition to items of ‘utility,’ like clothing, bedding, and toys, there was definitely an element of absurdity present in some of these donations. For instance, there was more than one letter that detailed large quantities (usually in the triple digits) of Hostess cupcakes being received by MTS for the ‘boys and girls.’ Surprisingly, there were also many fur coats received by the institution.

Writing these ‘thank you’s’ to Mansfield’s donors indicates a few things. For one, there was one point in time that this clerical gratitude was valued so highly at Mansfield as to itemize each component of a person’s donation (however, we have little knowledge as to how these donations were distributed or shared). Additionally, we know that at least some of these letters were read to members of an organization if the donation was made in the name of a group.

As is general knowledge, Mansfield, like most public institutions, were severely underfunded. To some extent, it is safe to assume that MTS was partially reliant on donations. Again, this piece does not aim to argue that the donations made were not valuable, but rather examine the underlying motives and implications of a person to donate to MTS, and for MTS to record those details in (cheerful) extremity.

So… what do we do with this information? Frankly, box no. 31 raised more questions than answers for me about the underbelly of MTS. How were these items actually used by residents? Were these all of the donations? Did donations to MTS cease in the years following this recordkeeping? Or do these letters indicate the origins of the UConn Foundation?

As we continue this excavation, hopefully the rhyme behind the reasoning for keeping records like these will become more clear.

To Abandon is to Forget

Written By Lillian Stockford

The abandonment of a place is the abandonment of its memory. When UConn acquired the land of the Mansfield Training School it also became one of the holders of its history. They have since left the memory to rot in the minds of the community and allowed the buildings of the campus to fall to pieces. They left records to decay on the floor of the Knight Hospital and we will never know what those records said or what pieces of the puzzle they could have provided. Instead, those abandoned documents had to be deemed irrecoverable after sitting for almost 30 years, from the closing of MTS in April 1993 to the spring of 2021. This disrespect of the documents is indicative of the larger trend concerning the property itself –and by extension, a grave disrespect for all the people who resided and worked there. Trees grow out from the underside of the buildings, rooms remain with fire damage, and fenced-off buildings are full of asbestos. An overall sense of desertion hangs over the campus.

“The Mansfielder” and the Publicity Machine

Written By Ally LeMaster

When I arrived on my second day of our archival visits at the Connecticut State Library, I felt like an archaeologist who exhumed only a few miscellaneous bones of an entire body. I spent my time in between archival visits scouring old Hartford Courant articles, watching videos of “urban explorers” documenting the haunting conditions inside of Knight Hospital, and researching other institutions to try and understand how each bone left behind at Mansfield Training School (MTS) connected. The more I found, the less confident I became in my ability to assemble the skeleton as it once was. I was determined that day to find something more than bones— this time I wanted to leave with a way to piece the story of MTS together.

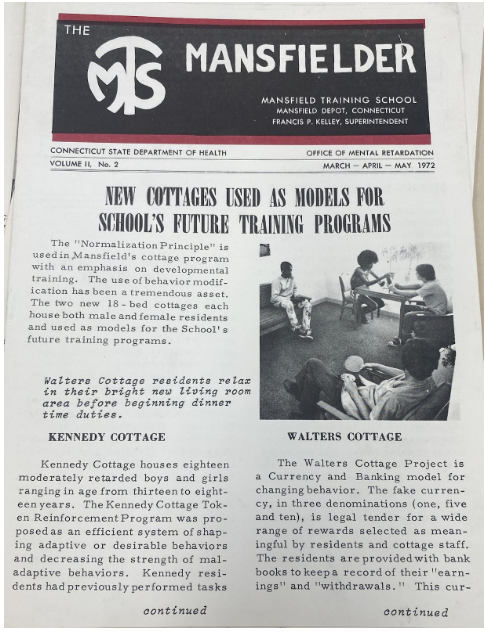

In the box I searched through, nestled between employee guidebooks and vaguely documented dismissal records, I pulled out a stark white booklet titled “The Mansfielder.” What first stuck out to me was the near-perfect condition these booklets were kept in; many of the documents the research team and I went through were in various states of aging, with most of the files I looked at printed on thin, transparent copy paper. There were dozens of editions of The Mansfielder scattered throughout folders, with some of the same issues even having multiple copies.

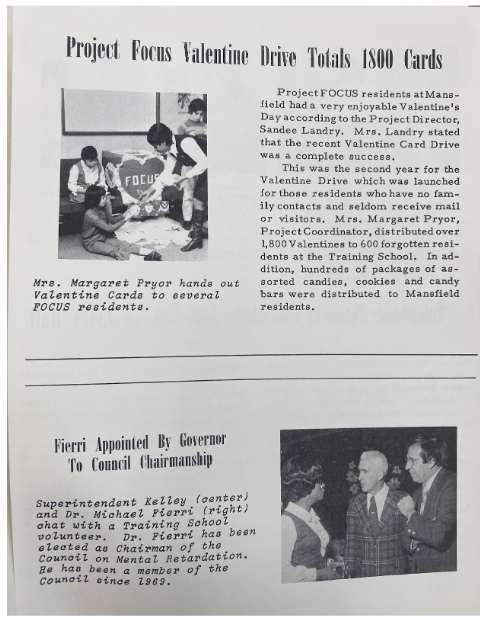

Two editions of the Mansfield Training School’s published newsletter “The Mansfielder.” These two issues span from March through September of 1972, highlighting stories such as the construction of new cottages for residents and a Valentine’s Day card drive. Copies of “The Mansfielder” were sent to institutions across the United States, state government officials, and families of the residents.

What I originally believed to be the first edition of The Mansfielder was published in 1972 and was signed by superintendent at the time Francis P. Kelley. Kelley’s time at MTS was marked by his significant attention to public relations, often having legislators, academics, and journalists visit and take guided tours of the institution. The Mansfielder followed exactly what Kelley had set out to do: it gave Mansfield Training School the positive public perception it was desperately in need of after Geraldo Rivera’s exposé of the abuses at Willowbrook State School released that same year.

Each edition of The Mansfielder followed residents and their activities over the course of a couple months and were littered with syrupy sweet headlines:

“Project FOCUS Launches Roller Skating Program”

“Mansfield Artist Sketches Portrait of Governor”

“Project FOCUS Celebrates First Anniversary With Holly Ball”

“Residents to Make Christmas Decorations for Trees”

“Training School Employee Honored as ‘Outstanding’ by the AAMD”

“Technical School Builds Cabins For Summer Camp”

(Project FOCUS or “Forgotten Ones Christmas You Serve” was a program through MTS in the 1960s that started as a way for the University of Connecticut faculty to take “unvisited” residents home for the holidays. It later became a year-round project involving foster grandparents, outings, and donation drives.)

Each headline strikes the balance of positivity and productivity; giving the reader the illusion that a day at Mansfield Training School was filled with hard work and hard play: a narrative that strayed far from reality.

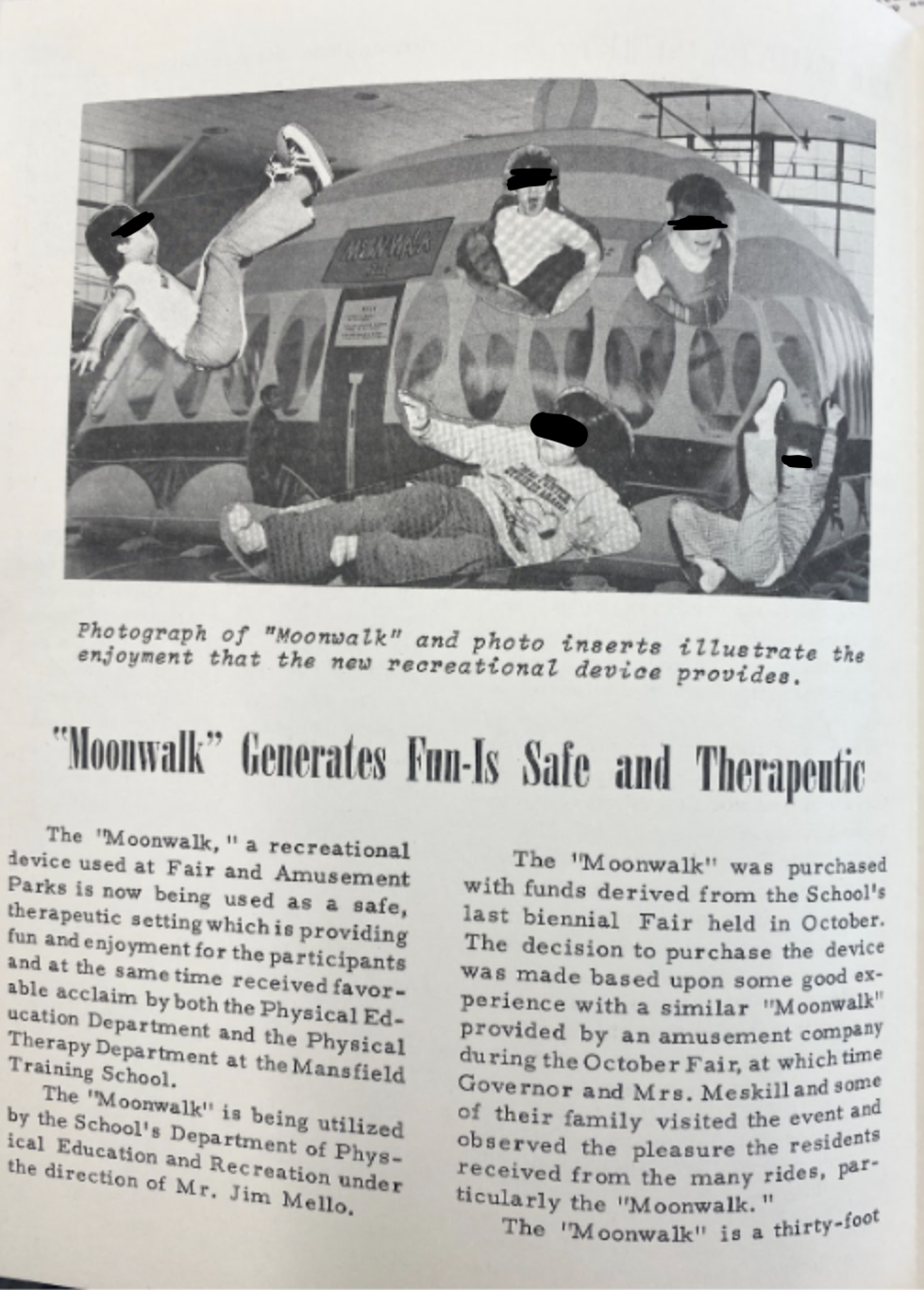

The thin veneer of The Mansfielder begins to dissipate the further you dig into the publication’s issues. The article titled “ ‘Moonwalk’ Generates Fun– Is Safe and Therapeutic” is accompanied by a photoshopped image of residents cut-out and pasted over a picture of a bouncy house to “…illustrate the enjoyment.” The article itself focuses on the physical benefits and fun of the residents’ new bouncy house, but excludes interviews or real-time photographs of the residents actually enjoying it.

In the article “Project FOCUS Launches Roller Skating Program,” The Mansfielder celebrates the donation of 51 pairs of roller skates with a party, but fails to mention how many of the 629 Project FOCUS members used these skates or how long each resident could skate for.

While most of what The Mansfielder spewed out to Connecticut governmental agencies, resident’s families, and other state institutions veered on the line of propaganda, some articles added new life to other documents the research team thought were only dead ends. Before discovering The Mansfielder, I read about new cottages and apartments built by MTS, but found no further information, which led me to believe they simply didn’t exist. However, many of the articles in the publication spotlighted the different out-of-facility living arrangements; their locations, their usages, and which residents were eligible. In addition, the last publication under Kelley’s reign printed out part of his resignation speech, listing what he believed MTS needed to improve on for the future.

The most out of place article in The Mansfielder is titled “Connecticut Legislators Inspect Training School” and describes the awful conditions 55 legislators found while touring the school in 1973:

“The units showed the passage of time with cracked and falling plaster, leaking roofs, crowded living areas and and in general an unpleasant, uninspiring atmosphere. These were units that had been recommended for demolition by previous committees. They saw toilets without seats, ‘gang showers’ and a general lack of privacy…”

At the end of this damning article, The Mansfielder still tries to spin the narrative, “ The feeling among Legislators was that change was necessary and that change must be positive and immediate!”

That article left me with many questions. In the time of institutional exposés, why publicize various problems in a publication meant to showcase the best of the Training School? Is it to garner more donations? Create sympathy? Actually address a problem?

Did The Mansfielder choose to include the least harmful discoveries of the visit? Is the truth of Mansfield Training School so bleak that a positive angle can’t even cover the direness of living conditions?

Will we ever really know?

For a while, I believed The Mansfielder did something other archival documents could not: add to my bones of understanding with muscle and scar tissue— build a fuller story of what happened at MTS. When you create a narrative, albeit a distorted one, you add life to someone’s story that would only be told through numbers; age, years spent at the institution, prescribed milligrams of medication, and time spent in physical restraints.

But that’s the problem. That’s exactly what makes publications like The Mansfielder so dangerous. Any entity who is given the power to be the sole storyteller of another’s life has the ability to make the ugly parts disappear forever. It’s so easy to create an inaccurate perception of the truth as long as you have an interesting story. So how can I lay out the complete story of the body when it was never allowed to speak for itself?In other words, I don’t believe we can exhume the body and reassemble it because the body wasn’t a body to begin with. The truth of Mansfield Training School begins and ends with its residents: people who had lived experiences that we will never fully understand because we were always made to forget. The purpose of doing archival research on institutions is not to recreate stories of residents, otherwise we’d be just as bad as The Mansfielder. Our work is built on challenging erased narratives by analyzing information and providing real accounts to what real residents went through. Our narrative is their narrative. All we can do is provide you with context from what we’ve learned.

Poetry of the Institution– A Closer Look of MacNamara’s Poetics

Written By Madison Bigelow

During Summer 2023, the entire research team co-authored a blogpost with our own reflections on Superintendent Roger D. MacNamara’s analysis of the Mansfield Training School closure in 1993, titled “The Mansfield Training School Is Closed: The Swamp Has Finally Been Drained.” Warmly referred to by our own team as “Dayton Drains the Swamp,” this op-ed explores what seems to be MacNamara’s attempt to make peace with his own involvement in the atrocities that took place during his time as head of MTS’ administration.

Amongst the many fascinating things that MacNamara has to say about the school’s closure and his experiences as superintendent, something that deeply struck me about his piece comes near the beginning of the article: a quote he includes from the book titled Souls in Extremis (1971), which is Burton Blatt’s analysis of the inhumane conditions of institutions that house the mentally and/or physically disabled. MacNamara introduces this quote by stating that “Blatt included a piece of my free verse in the foreword [of his book].”

The quote reads: “Backward stranger, you have story to tell without words we can understand. Never thought to possess human needs,your only gifts are isolation and desolation. Your life in a porcelain cage is nonexistence, interrupted only by the madness of your sisters’ struggling spirits. Can you hear the people talk of change only to see compassion left at the door step? How could you know that the reforms never left committee? Growing old and inwardly dying each passing day, why can’t you accept injustice in silent agony, as we were told you would. The sands of time create the glass you shatter, and you turn on your own irreplaceable flesh in self-inflicted torture, which on one understands to be your message to the planners: ‘I will render my flesh disfigured and blur my consciousness while you are powerless to stop me. Your consciences do not allow you to bind me, but your senses cannot tolerate my destruction. When you find the answers and have the means, I will be waiting here for my new life. I’m not going anywhere.’”

To be frank, my eyes sort of glazed over this portion of the op-ed when I read it on my own. Because this quote appears on the first of four pages, I found myself skimming over this portion to find his direct criticisms of the Mansfield institution. However, hearing Brenda speak these words out loud during our group-read of the piece, I started to become deeply curious about the rhetorical implications of MacNamara’s choice.

It is important to note that this quote is, in fact, an excerpt written by MacNamara himself that appears in Burton’s forward (which… must’ve required a lot of self-admiration, to say the least). To acknowledge that this quote is explicitly and intentionally written in free verse begs the question: why does a poem appear in the middle of MacNamara’s serious meditations on MTS’ shutting down for good?

Granted, this excerpt doesn’t read like a poem in the most ‘traditional’ sense. It lacks any sort of end-rhyme scheme, line breaks, or a ‘standard’ rhythmic cadence that one would expect from poetry. However, MacNamara explicitly notes this quote as a work of free-verse. Maybe this is a fast and loose employment of the term. But, especially since MacNamara acknowledges his own writing (and the intent behind it) as a work of free-verse in “Dayton Drains the Swamp,” I think it deserves the respect of being read as poetry, if just for a thought experiment.

To perform a brief analysis on the excerpt above, MacNamara’s ultimate goal in his self-quotation is to foster a deep-seated feeling of sympathy towards the residents of Mansfield. The repeated address of the second person implicates the audience in temporarily assuming the role of the disenfranchised; as MacNamara asks “Can you hear the people talk of change only to see compassion left at the door step?” to leverage the viscerality of his audience’s sympathy for the residents that is much quieter in the rest of the piece.

In the second half of the poem, he switches perspective and adopts the voice of the institutionalized. Concluding the excerpt with the statement “‘When you find the answers and have the means, I will be waiting here for my new life. I’m not going anywhere,’” MacNamara further calls upon the sentimentality of his audience in a very interesting way; he assigns and articulates the voice of the masses that have been excluded from the conversation of deinstitutionalization up until this point in time. A voice, in other words, that many have been willing to argue ‘for the sake of’ but very hesitant to listen to.

The use of metaphor here, too, is particularly thought-provoking. In such a clinical, sterile, and otherwise professional space that was the Mansfield Training School, a former leader of the administration himself chooses figurative expression above any other method to communicate his thoughts regarding institutionalization. While he cites concrete observations about the abuses, corruptions, and hypocrisies of MTS later in the op-ed, the choice to firstly ground his position with a poetic excerpt speaks volumes.

Comparing life in the institution to “life in a porcelain cage [as] nonexistence, interrupted only by the madness of your sisters’ struggling spirits” suggests that the happenings at public institutions across the country are almost too atrocious to be spoken about. By adopting such a poetic vehicle to exemplify the deepest iterations of these abuses upon residents housed in these facilities, it seems that MacNamara specifically utilizes free verse as a vehicle for expressive thought when other methods have failed.

I acknowledge, though, that this insight is completely formed as a result of my biases– I love poetry, and I look for poetry in everything. Maybe even in places where poetry doesn’t ‘exist’ (although, that’s another conversation). However, the intentional use of poetry as a tool to approach institutionalization and the humanity of its residents that is integral to remember, but often forgotten, cannot be ignored. Despite all of the legal proceedings, government hearings, and standard procedures that illuminate the legacy of the Mansfield Training School, the actual ‘issues’ surrounding MTS concerned people. People with emotions, with feelings, and with experiences that can’t be genuinely shared in an administrator’s testimony.

To me, MacNamara tries to voice the experiences of others – specifically the institutionalized that have been denied their voice from the origin of MTS to its closure – and mobilizes poetry as a means to convey a sympathetic appeal to his audience similar to if a resident would have spoken. Of course, his attempt isn’t perfect. Clearly, the excerpt is written by an individual who is very well-read and has knowledge of life inside AND outside the institution from a bird’s-eye view.

But MacNamara pulls back the curtain, if only for a brief moment, and sheds light on the possible emotional state of many residents themselves. In an ideal world, residents and others involved in institutional life would be directly invited to these testimonies, conferences, and other conversations concerning their ‘well-being’ and trajectory of their institution. This clearly didn’t happen, or else we would see residents’ names in the historical records. However, MacNamara does provide an insight to his colleagues and peers about the internal soul of the institution that they presumably would’ve never considered otherwise, had it not come from his mouth.

Ultimately, metaphors resonate; they’re able to explicate and convey iterations of the human experience that could never be contained by a standard procedure. And, as a whole, poetry illuminates. It elucidates sentiment, sensation, and incidence. Establishing these metaphors sets the tone of the piece and serves as an emotional anchor point for many of the events leading to MTS’ closure in the 90s.